In Indian cuisine, dal (also spelled daal or dhal in English; pronunciation: [d̪aːl], Hindi: दाल, Urdu: دال), paruppu (Tamil: பருப்பு) or pappu (Telugu: పప్పు), are dried, split pulses (e.g., lentils, peas, and beans) that do not require soaking before cooking. India is the largest producer of pulses in the world. The term is also used for various soups prepared from these pulses. These pulses are among the most important staple foods in South Asian countries, and form an important part of the cuisines of the Indian subcontinent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dal

Here in the United States most of us know dal as an Indian stew or soup made of red lentils. Technically this is true, but in India dal is first and foremost the word for all small legumes- lentils, mung beans, peas… there are over 50 varieties of pulses known on the Indian subcontinent. Most commonly dal refers to the split version of the seed, although sometimes whole pulses are also called dal. Dal, then, also refers to dishes made with these pulses.

The most common preparation, and by common we mean eaten daily by nearly everyone in India, is a simple dish consisting of cooked dal with tomato, ginger, green chilies, and spices. For a country with 1.4 billion people divided into 2000 ethnic groups, the basic recipe remains surprisingly uniform, at least across the 70(!) different recipes I looked at. Granted that’s only across 10 or so websites, so there’s maybe some element of the author changing the legume and calling it a new recipe going on. (Or maybe some plagiarism? I also noticed that across several different large websites, the language used in the blog post part of the page was pretty consistent- whether that’s SEO at work dumbing down every website on the planet to “optimize” it for search engines, third-party “content creators” ghostwriting websites by copying other websites, or just plain lazy blogging I don’t know.)

Anyway, yes, the red lentil dish we know and love in North America is a type of dal, but in India, it isn’t necessarily the most popular one. Out of 50 different dals known in India, there seem to be four that stand out as the most popular. In order, as best I can tell, they are toor dal (aka toovar dal, arhar dal, or split pigeon peas), moong dal (split mung beans), chana dal (split chickpeas), and finally the above-mentioned red lentils, masoor dal (which are actually split and hulled brown lentils.)

Pretty much all dals come in three forms- whole, split with hulls intact, and split with hulls removed. The split, hulled versions are most commonly used. Although removing the hulls may remove some nutrients, it is intended to increase digestibility and palatability. Removing the hull increases available protein, and reduces fiber. Of course, pulses with the hulls intact are also popular.

Every Indian household (or at least the ones well off enough to spend time blogging about their food) seems to own a pressure cooker and use it to cook their dal. To my mind, adjusted to cooking larger beans that take an hour or two to cook on the stovetop, that seems kind of silly since most small pulses will cook in 30-40 minutes without soaking, so by the time the pressure cooker comes up to pressure and cools down again I don’t know that you’ve saved more than about 5 minutes. I suppose when you’re cooking dal three times a day saving five minutes adds up. Anyway, in the spirit of authenticity, I did follow along and wrote my recipe for the InstaPot. If you have a stovetop pressure cooker the timing should be about the same, and for non-pressurized cooking, you’ll probably need to add some extra water as your dal cooks, and it will take 25-45 minutes or longer, depending on the type of dal and how old it is.

There are two traditional ways of making everyday dal: dal fry and dal tadka. For dal fry, the lentils are cooked on their own, with maybe a pinch of turmeric, and then the remaining ingredients are sautéd (aka “fried”) and the cooked pulses are mixed in and cooked together briefly. In dal tadka, on the other hand, the vegetables and some of the spices are sautéd first and cooked along with the lentils, and then the dish is finished with a tadka or tempered oil (or one of at least half a dozen other regional names). Spices are tempered in hot oil or ghee and then the sizzling oil is poured over the dal. A number of the InstaPot-based recipes I looked at took it to a one-pot method and just cooked everything together. My recipe falls somewhere between the one pot and tadka method- I do make a tadka, but probably put more spices into the pot in the earlier steps than is strictly authentic for that style.

The other reason many cooks liked the InstaPot is the ability to do “pot-in-pot” cooking, cooking rice at the same time by placing a heat-proof bowl with the rice and water on a trivet above the dal. I have not tried this yet but include instructions if you want to.

There are, of course, several exotic ingredients beyond the dal itself that go into this dish. If you don’t have a good Asian/Indian grocer near you (I don’t) I found them all on Amazon.

Ghee is one of the most common cooking fats in some parts of India. Ghee is basically clarified butter that has been allowed to brown ever so slightly before the fat is separated from the milk solids. It’s relatively easy to make your own (I’m sure there are thousands of recipes on the internet), but we had a jar of commercially produced ghee that my wife bought for something and never opened so I just used that. Although many people with dairy sensitivity can eat ghee, if you can’t or if you are vegan, you can absolutely substitute any neutral-flavored cooking oil, coconut oil, or mustard oil. Don’t use olive oil if you’re looking for authentic flavors though.

As far as the green chilies go, I used serrano peppers. Most of the recipes I looked at said you can use serrano, jalapeño, or Thai chilies. I think that in India the common green chili is about the diameter of a serrano, but longer and lighter colored, and I have no idea as to the spice level. Obviously, you should adjust the quantity and variety of chilies and chili powder you use to fit your own preferred spice level.

Asafoetida is the dried latex or gum resin obtained from the roots of several species of ferula, a plant in the carrot family. Its name comes from Persian azā, meaning mastic, plus Latin foetidus, stinky, and it does indeed have a somewhat strong odor, which dissipates when cooked. It lends a flavor reminiscent of onion or leeks to dishes. A little goes a long way, so you’ll only use a pinch or two in any given dish. Because it is a sticky resin it is usually mixed with a starch, often wheat, so if you are gluten intolerant find a gluten-free brand or skip it.

Curry leaves are the leaves of the curry tree. They are unrelated to Western “curry powder” which isn’t really a thing in India. The leaves are relatively sturdy, not quite as thick as a bay leaf (you can eat them once cooked). I ordered fresh curry leaves on Amazon, and they arrived in relatively decent shape despite not being shipped with any kind of insulated packaging and getting lost in the mail for four days. There were some wilted/slimy leaves, but the majority were still in good condition and should keep for quite a while in the fridge wrapped in paper towels in an airtight container.

Most of the recipes I looked at called for a “large tomato” and then said something like ⅓ to ½ cup, which doesn’t match up to what I would call a large tomato here in North America. I believe that perhaps they are using Roma-type tomatoes, which is what I did. (Similarly, I think that the onions commonly used in India are much smaller than what is standard here in the West, but I went ahead and used a medium-sized by Western standards onion.)

The red chili powder called for in Indian recipes (or really any cuisine outside of Tex-Mex/ American usage) is pure ground chili peppers, NOT the blend of spices used to make “chili”. Kashmiri red chili powder is supposedly milder than other varieties, and that’s what I used. It’s still got what I would call a pleasant kick, and my wife would probably call “my mouth is on fire”. If you don’t have Indian chili powder you could use cayenne pepper, but cut back the quantity significantly.

Kasuri methi is dried fenugreek leaves. It really adds a distinctive, delicious flavor to the dal, but be warned my hand still smells like fenugreek two days after crushing the leaves!

Although “curry powder” isn’t a thing in India, there are many other spice blends, or “masalas” used in different regions. Traditionally these would be something each cook would make their own version of in small batches, but I’m sure in the 21st century pre-made versions are commercially available in India just as readily as spice blends are in the West. The most famous of these masalas, outside of India, is of course garam masala. This North Indian spice blend is a mix of sweet and warm spices like cardamom, cinnamon, cumin, cloves, and peppercorns. It’s generally added to dishes at the end of cooking to keep the flavors bright. In recent years this has started to become a more common option in American supermarkets, even in smaller cities without large Indian populations.

Dal is traditionally served with rice and/or roti, chapati, or naan. I chose to make roti.

Dal

Serves: 4

Prep: 15 minutes

Cook: 35 minutes

Total:50 minutes

¾ cup toor dal

OR

¾ cup moong dal

1 ¾ Tablespoons ghee

OR

1 ¾ Tablespoons vegetable oil

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1-2 green chilies, chopped

¾ inch fresh ginger root, grated

3 cloves garlic, minced

⅛ teaspoon asafoetida

12-15 curry leaves

1 yellow onion, diced

1 large Roma tomato, diced small

½ teaspoon turmeric

¾ teaspoon red chili powder

1 teaspoon coriander powder

½ teaspoon kosher salt

2 ⅔ cups water

1 teaspoon kasuri methi

1 ½ Tablespoons cilantro, minced

5 teaspoons lemon juice

tadka:

1 ¾ Tablespoons ghee

⅔ teaspoon cumin seeds

1 pinch asafoetida

2 dried red chilies

3 cloves garlic, minced

½ teaspoon red chili powder

½ teaspoon garam masala

Optional:

¾ teaspoons black mustard seeds

1 ½ teaspoons ginger garlic paste, in place of fresh ginger/garlic

1 cup water to thin dal (or as needed)

¾ cup masoor dal (requires only 6-8 minutes of cooking)

¾ cup chana dal (will need 12-15 minutes cooking time)

1 Tablespoon lime juice, in place of lemon

Optional tadka ingredients:

½ teaspoon black mustard seeds

10-12 curry leaves

¼ teaspoon turmeric

Pot-in-pot rice:

1 cup basmati rice

1 1/3 cups water

½ teaspoon salt

Rinse dal 3-4 times, until water runs clear. Set aside.

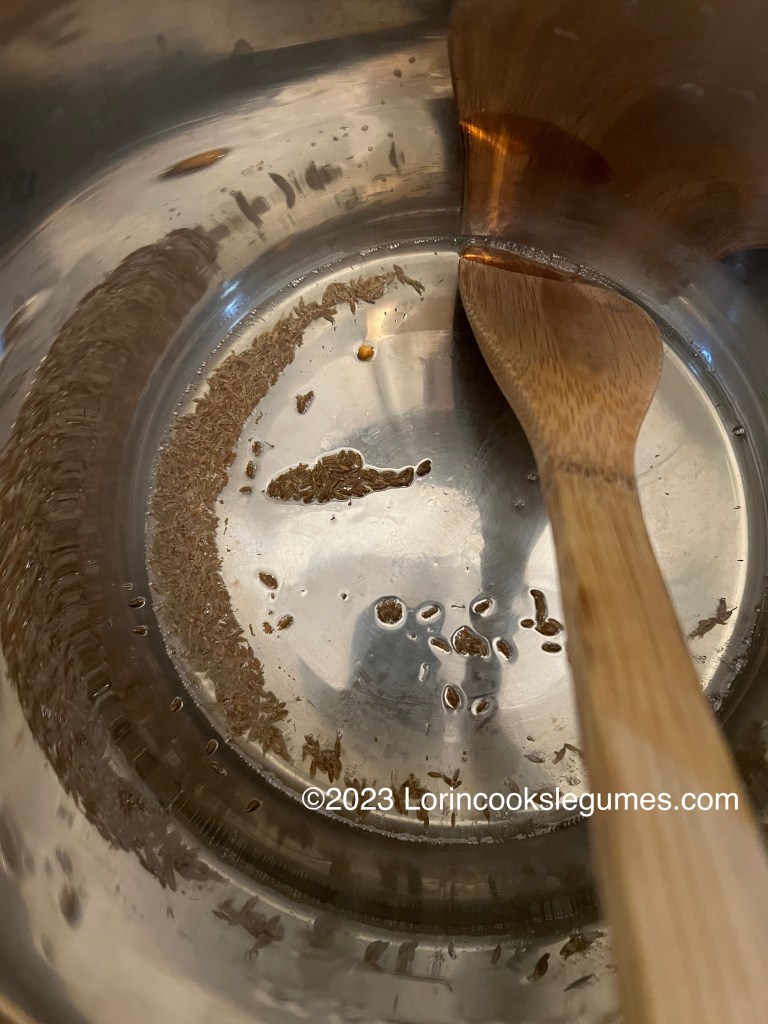

Heat your InstaPot on sauté setting. Add ghee or oil. When hot, add cumin seeds (and mustard seed, if using) and fry until they splutter, about 30 seconds.

Add green chilies, ginger, garlic, asafoetida, and curry leaves. Sauté for 1 minute, or until garlic no longer smells raw.

Add the onion and sauté until golden, 4-5 minutes.

Add the tomato, turmeric, chili powder, coriander and salt. Cook until tomato is soft and oil begins to separate from the mixture, 3-4 minutes.

Add the rinsed dal and water and stir well, scraping up any bits stuck to the bottom. Hit cancel on the InstaPot control panel.

(If doing pot-in-pot rice, see below)

Close the lid and set the vent to seal. Select manual pressure cook and set for 10 minutes (you can go a minute or two shorter or longer if you like your lentils on the firm side or very well done). When the cooker beeps, let the pressure release naturally for at least 10 minutes.

Carefully open the cooker. Crush kasuri methi between your palms and stir into the dal. Add cilantro and lemon juice. Stir well. Taste for salt.

For the tadka, heat ghee in a small frying pan. Reduce heat to low and add the cumin (and mustard if using). Cook for 30 seconds or so, until the seeds sputter. Add the asafoetida, chilies, and garlic. Fry until the garlic is golden, about 1 minute. Remove from heat and add chili powder and garam masala. Stir well and pour over the dal. You can stir it in, or leave it on the surface for presentation.

Serve with rice, roti, or naan.

For pot-in-pot rice: before closing the lid of the InstaPot, place a tall trivet in the pot with the dal and place a metal bowl with the rice, water, and salt on top. Close the IP and cook as above.

4 Comments Add yours